Style Strategy 007: The 'effortless style' paradox

It takes a lot of time and money to look like I didn't care.

When I was a full-time fashion magazine editor, there was almost no greater compliment to bestow than being called effortless. Sometimes, I’d have to strike it out of copy that came in because it got used too much; it’s a term that gets thrown around so much that all meaning behind it is lost.

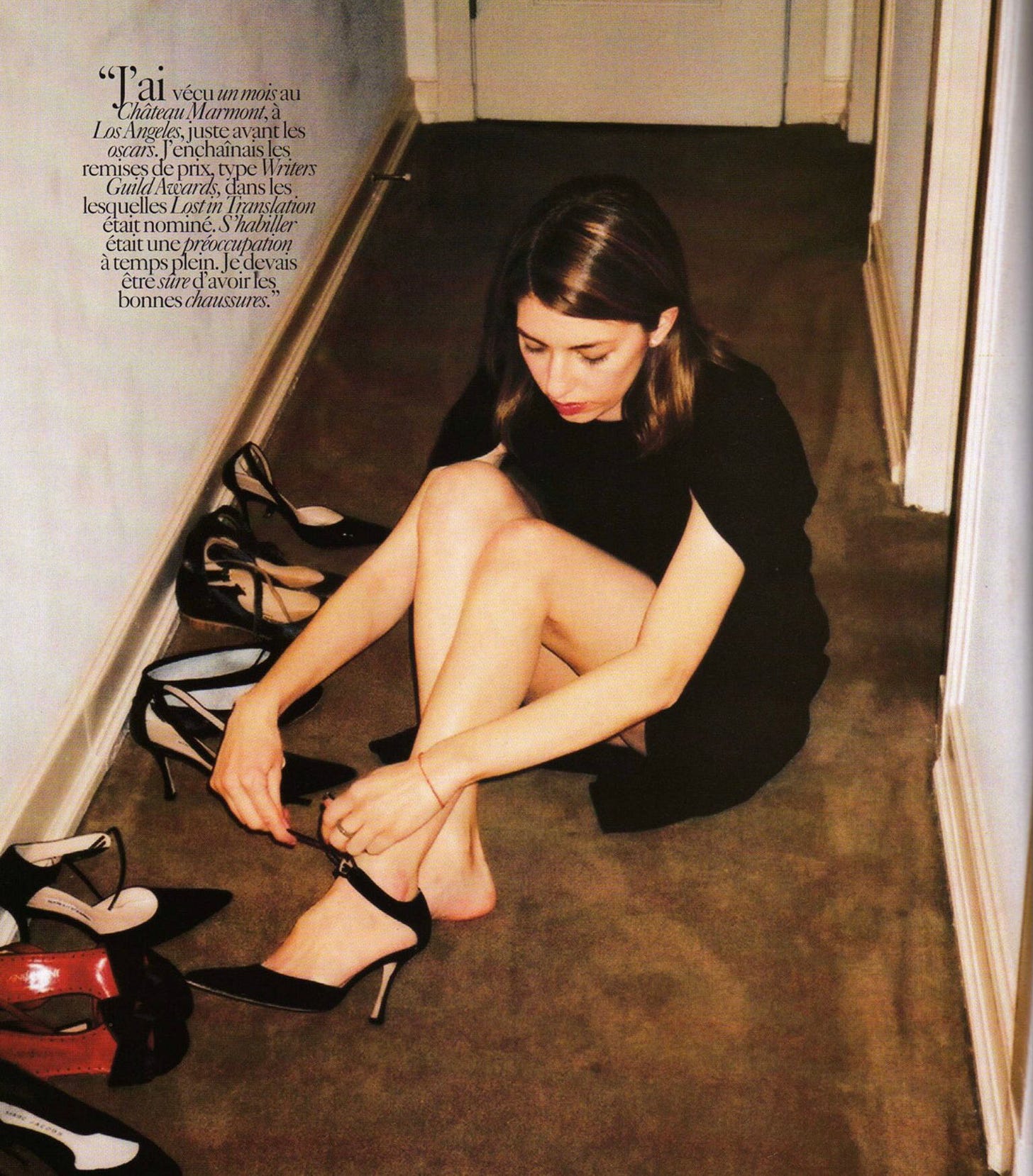

Zoe Kravitz. A white T-shirt underneath a crewneck knit. Lauren Hutton. Rolled-up sleeves. Tina Chow. A shawl draped like a cape. Caroline Bessette Kennedy. Flat shoes. Dressed-up fabrics worn with everyday textures. A clutch grasped at the top rather than the handle. Sofia Coppola. A hand wearing fine jewellery, shown eating fast food. Oh-this-old-thing. “It’s vintage!” etc. etc.

told the Wall Street Journal that clients, from CEOs to celebrities to laypeople, frequently ask for guidance on how to look effortless:“All my clients say, ‘I want to look styled and put-together, but I don’t want to look like I tried,’” said Bornstein, who has helped craft looks for women such as actress Katie Holmes and who splits her time between New York and Los Angeles. “Everyone wants to be effortless.” It is up to her to break the hard truth to her clients. “When you see someone whose style looks really easy, that usually means they put a lot of work into it,” she said.

Like Instagram carousel dumps which are meant to convey easy nonchalance even though they actually require careful curation, we already know that effortless style is a bit of a con, but we’re still drawn to it.

IT’S A CONTRADICTION

Effortlessness in dressing is the pinnacle — a sign of innate, unteachable style that suggests you were born with it, and yes, same applies to having a certain class advantage.

The French even have a term for it: bon chic bon genre (good style, good class), which makes a lot of sense when you think of the still-very-covetable yet narrow definition of ‘French girl style’ or ‘French girl beauty’, which is sold to us via ‘French girl beauty’ or brands like Sezane/Rouje/Isabel Marant. It’s also a contradiction because French girls that we think we want to look like still spend a lot of time on their fashion and beauty.

Nonchalance is great and all, but it helps to be beautiful.

Even French girls struggle with it. Take French writer Iris Goldsztajn on the ‘French girl’ ideal:

She exists, but she’s exclusionary by nature: white, skinny, affluent, city-dwelling, hyper-educated, and frankly a little snobby. For those of us who don’t fit her mould (and there are far more of us than there are of her), she is mostly a source of shame as we try and fail to be like her.

Here’s another irony. Why do we think trying or caring should be a secret? And don't forget the greatest sin of all — trying too hard.

But is trying too hard such a bad thing?

A counterpoint to the effortless ideal is ‘Jeremy Strong doesn't get the joke, a New Yorker profile that poked fun of how much of a striver he is and encouraged the rest of the internet to join in on the joke. “I’d never met anyone else at Yale with that careerist drive,” one of his classmates chimed in, before the quote that took off: “Other peers recall a more ingenuous superstriver.”

Effortless, he is not. His trying-hard-ness extends beyond his career to his dress sense as well: “I’ve just always loved clothes,” as he tells GQ. “I’ve always felt in a very primal way that, probably all of us here, that it's such an immediate and palpable way of expressing something about ourselves. I care about aesthetic and I care about how something is expressed, and it's a pretty narrow aperture for me.”

A NYT opinion piece in defence of Strong’s striving points out that effortlessness — like bon chic bon genre — is inherently a class issue. I think about these two articles frequently, and the tension of visibly trying hard being something to be maligned.

Elites are often socialized into affecting “ease” and eschewing displays of effort. But it’s a mistake to see the disconnect in terms of personal style or etiquette. We strivers cannot behave as if things come easily because pretending that they do often requires resources we lack. We are “unchill” because we have neither the time nor the money to assemble the accouterments of chill, or to perform it.

This cultural bias against striving extends to fashion.

To affect ease, it’s about having the right resources — money, time and social capital and general in-the-know-ness — to perfect the art of not being a try-hard. To succeed in the pursuit of effortlessness you must master illusion — conceal all the work behind the pursuit.

The Italian word sprezzaturra captures this studied nonchalance. The term was first used in 1528 by Italian courtier Baldassare Castiglione in The Book of the Courtier, a guide for gentlemen on how to achieve understated sophistication. Sprezzaturra was about how a courtier’s tasks needed to look effortless even if it’s difficult, and applied to how one dresses or even a performance — fitting, since the act of dressing is always inherently a type of performance, whether for ourselves or for an audience.

The truth is, effortless is not about opting out of trying, but having the privilege to hide the work of trying.

BECAUSE IT’S MODERN

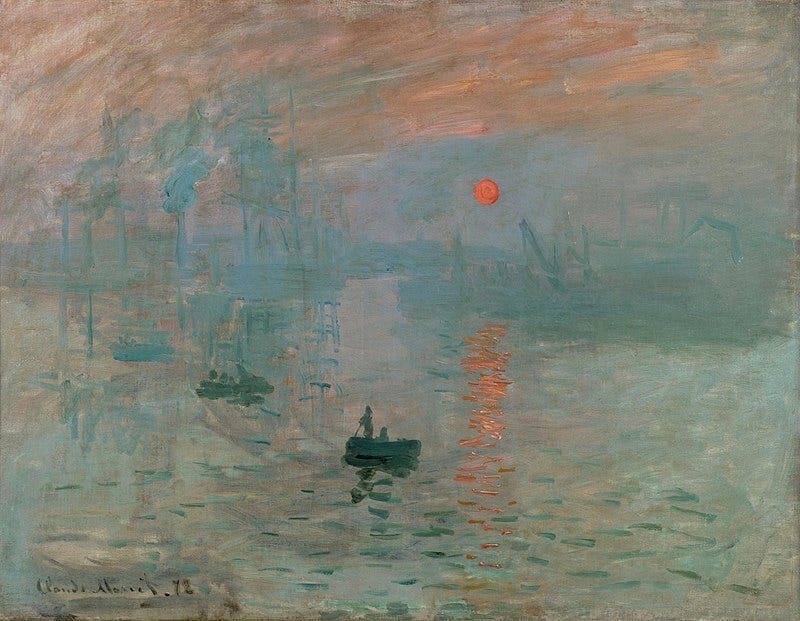

This obsession with disguising effort isn't new. Historically, it has defined notions of modernity and rebellion in art and fashion. The Impressionist movement sprung out of the late 19th century when a group of artists banded together to showcase their work. Their work had been rejected by the Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris because they in turn rejected artistic conventions: instead of historical paintings they painted modern scenes, and instead of realistic portrayals they were instead ‘impressionistic’ with loose brushstrokes.

Now we know Impressionism as one of the most popular mass style of art (art museum people joke that a ‘Monet exhibition’ is really a ‘mon-ey exhibition’ because it’ll guarantee loads of ticket sales). It was rebellious, and it depicted everyday life. Much like the original Yves Saint Laurent’s embracing of trousers for womenswear, or Coco Chanel eschewing corsets for looser silhouettes, it's the departure from tradition makes something modern.

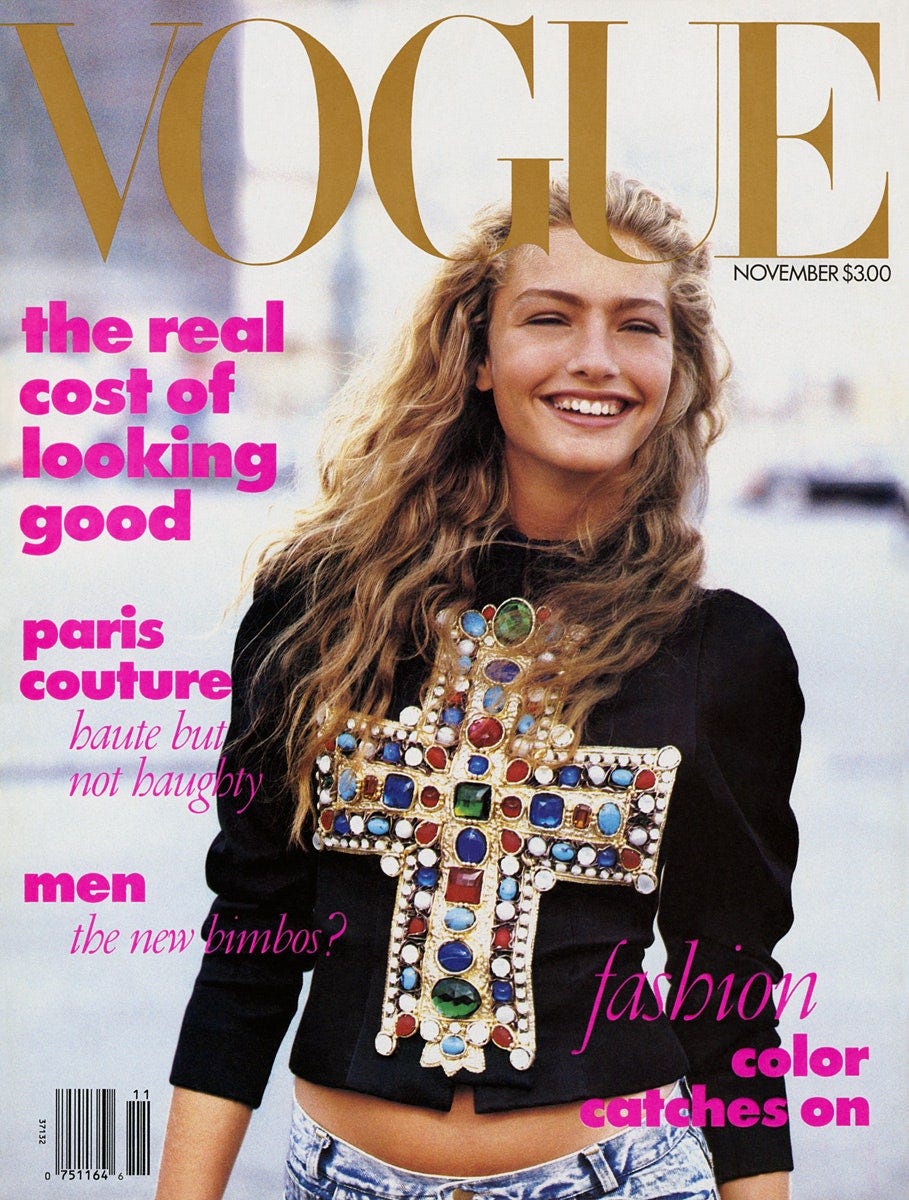

We see this in how we dress too — Anna Wintour’s famous first cover of a haute couture Christian Lacroix jumper worn with denim was, and still is, very modern. Today? It’s brands like The Row and Phoebe Philo that have come to define effortlessness as a marker of refined taste, provided you have the wallet capacity to regularly purchase it.

EFFORTLESSNESS CODED AS ‘I’M TOO SMART TO CARE ABOUT FASHION’

The idea that it’s considered ‘dumb’ and frivolous to like fashion and beauty stems from systemic biases that devalue interests traditionally associated with women in favour of the more ‘masculine’ like politics, science or sports which are often seen as more serious or intellectually valuable. Admitting that I like fashion or beauty — which is considered to be about outward appearances — reinforces negative stereotypes of women as vain or self-absorbed, and then internalised sexism reinforces these beliefs. So — dismissing fashion and beauty can feel akin to aligning oneself with societal standards of intelligence and respectability. Somehow it always comes back to Andy’s lumpy cerulean sweater as a signifier of her disdain for fashion.

Take Zadie Smith, who famously implemented a ‘15-minute rule’, which forbade her family from looking in the mirror for more than 15 minutes a day, sparked by her seven-year-old daughter inspecting her reflection:

“I decided to spontaneously decide on a principle: that if it takes longer than 15 minutes don’t do it,” she said. “I explained it to her in these terms: you are wasting time, your brother is not going to waste any time doing this. Every day of his life he will put a shirt on, he’s out the door and he doesn’t give a s— if you waste an hour and a half doing your make-up.”

“From what I can understand from this contouring business, that’s like an hour and a half and that is too long… It was better than giving her a big lecture on female beauty, she understood it as a practical term and she sees me and how I get dressed and how long it takes.”

Which is all very well and good, but Smith is also inarguably stunning to start with so has some privilege to act in a way to attempt to deflect from her looks.

From W magazine:

Here’s the problem, though: Smith—like no-makeup advocate Alicia Keys and the supermodel Natalia Vodianova—is an unequivocally beautiful woman with or without makeup—something she’s well aware of, having expressed her frustrations that her attractiveness has historically made people think she “couldn’t possibly be a great writer.” And by not giving Kit “a big lecture,” Smith might make the seven-year-old feel that she herself is the one to blame, rather than the system itself with its unrealistic beauty expectations of women.

I KNOW IT’S A CONUNDRUM

Maybe it’s a faux pas to admit this, but, I do want to present that I’m smart, even if I don’t always feel like I am.

I used to think I wanted the effortless style of ‘natural hair, throw on a pair of jeans and T-shirt and get out the door’. I’ve since realised that this approach frankly does not suit me. Maybe it reads as chic on some, but on me it reads as dishevelled.

Maybe living in the Western world makes us more influenced by Western values, but the conventional understanding of effortlessness in my milieu does not work on me, being very clearly non-white. In a Western-dominant society, ethnic minorities often feel like they have to try even harder to overcome preconceptions and societal obstacles.

And another irony: I’m aware of the conundrum of writing a fashion and style-focused newsletter that covers fashion and style that, for the most part, shares advice on how to distill a sense of personal style relevant to how we live today. And I know that often means the pursuit of some level and form of effortlessness — this is the modernity that is needed for a semblance of contemporaneity relevancy. But being aware of this conflict actually strengthens personal style. By knowing what I don’t want to tell the world through my style, I learn what I do want to say. It’s not about mimicry or social signifying. I want to show ease, confidence, originality and authenticity — and chances are, it’ll take a bit more time to put it together.

Genuine personal style for me may not lie in the pursuit of effortlessness, but in understanding the effort required to reflect ease, confidence, originality and authenticity. It’s not about hiding the work — but embracing it.

IF YOU ENJOYED READING THIS, YOU MIGHT LIKE:

The complexity of personal style

What made Chung, Chung, and what made Tina Chow so Tina Chow and Elsa Perretti so Elsa Perretti and Kate Moss and Gloria Guinness and Lee Radziwill and so forth and so forth, was that they were wholly and entirely themselves. They were a little bit less varnished, and not organising entire shoots to beam their imagery around the world. Back then there wasn’t so much #sponcon or ‘image architects’, and instead some of Kate Moss’ most famous outfits were from thrift stores, not designers. She plucked it out from a market, and made it entirely her own. (See below to hear her talk about some of her most famous looks. She holds thrift items to the same level of esteem as a runway sample.) Clothes as part of your personal style is a form of communication, and now you have the opportunity to call in help rather than doing it yourself.

The search for good taste is a trap

The concept of taste — good, or not — is amorphously slippery. What is taste, really — it’s the through line of reasoning of when you like something, the theme that holds your aesthetic opinions together. You can’t see it, smell it, touch it (or taste it — pun!) but you have a sense of it.

Are you born with your taste, or is it cultivated? Can it change? And if it does change, is it true to you? And, now, in a world where there is so much information all at once through the world wide web, can you really know what your taste is?

Introducing 'Style Strategy' - a series on how to define your taste and personal style

If you have been a reader of Screenshot This for a while, you may have noticed a common thread: talking about personal style. What it is. How to grow it, evolve it, how to do your own thing in the face of — and with, even — trends.

I love how detailed this was.

The other day I saw some quote about how “no man can resist a woman in a baseball cap” (this same type of effortless ‘oh I just threw this on’ vibe) and in my head was like…Yeah, if she is otherwise beautiful & feminine, and has long thick hair cascading from under the hat. AKA a woman who would be seen as attractive no matter what she was wearing.

But the class implications here are very interesting as well. I love when an outfit breakdown is like “Oh this is just my grandmother’s old Chanel handbag” as though that’s something everyone has floating around in their closet if they were just cool/smart enough to find it.

I really enjoyed this. Telling young girls not to care about their appearance lacks so much nuance. God knows a lesson was never instilled in me that way.

The idea of “effortless” is definitely a Eurocentric ideal, because in some cultures, it’s important to look like you’re trying. When I was younger, I bought into a lot of what I saw in mainstream media and magazines, but as I’ve gotten older—and am living in Nigeria again—I’ve developed more appreciation and respect for effortful dressing and style. I’ve tried to do my lipstick like a French girl…you know, dabbed on softly with no discernible lipliner and yeah no I just look unkempt.